Seven of us gather on a misty afternoon to explore our responses to Mary Oliver's work. Some read

Owls and Other Fantasies, some

The Truro Bear, some

Evidence. So many wonderful comments and ideas tumbled over one another, like pebbles in a rushing stream.

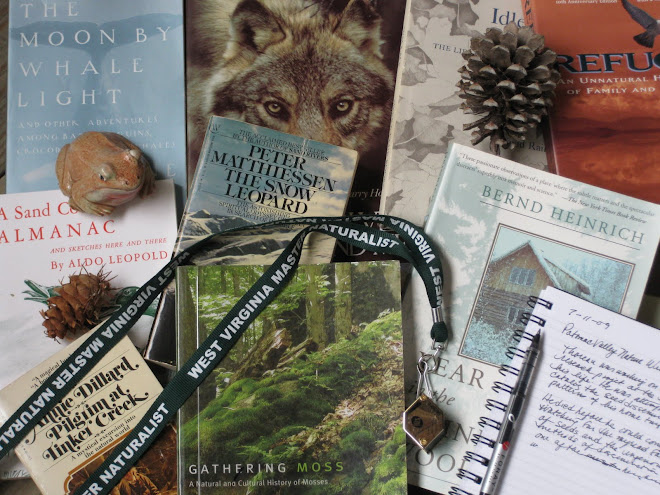

We debated whether Oliver's sensibility as a poet, as an artist in love with the sensuality of nature, is as valid a "way of knowing" as the empiricism of Bernd Heinrich. Oliver's approach resonates much more with some of us in our group than others. But no one denies having had at least one of those transcendent experiences in nature that Oliver evokes so well.

We identify that of the writers we have read, those who seem to write most powerfully somehow combine the scientist's passion for facts with the perceptions of their emotional and spiritual selves: the artist and the scientist dancing within one person, the artist-naturalist. We consider male writers we have read who are in touch with their "feminine side" as one member puts it. Oliver is most closely compared to Terry Tempest Williams, Rachel Carson and Robin Wall Kimmerer, all writers who embrace a holistic experience of nature, using their whole selves, the intellect, the body, the soul, and the imagination. It makes sense, considering that we humans are products of nature. Just where does the line between nature and non-nature lie?

The question arose, what are emotions for? Why do we have them? Is it nature or nurture? When we see wild geese winging their way in an undulating V, we respond with a catch in the throat. Is this because we associate it with some pleasant individual childhood memory, or because we--as a species, as mammals-- have co-evolved with nature, with migrating birds who foretell winter or joyous spring, for millennia? Is the study of our response to nature just as important as the study of non-human nature, perhaps these days even more important considering human driven climate change and escalating extinctions?

Mary Oliver invites us to deepen our experience of the natural world and embrace our "place in the family of things."